The Duanwu festival is known as the Dragon Boat festival named after the popular activity of dragon-shape rowboat racing during the festival.

Did the Duanwu Festival Really Originate From the Death of Qu Yuan(屈原)?

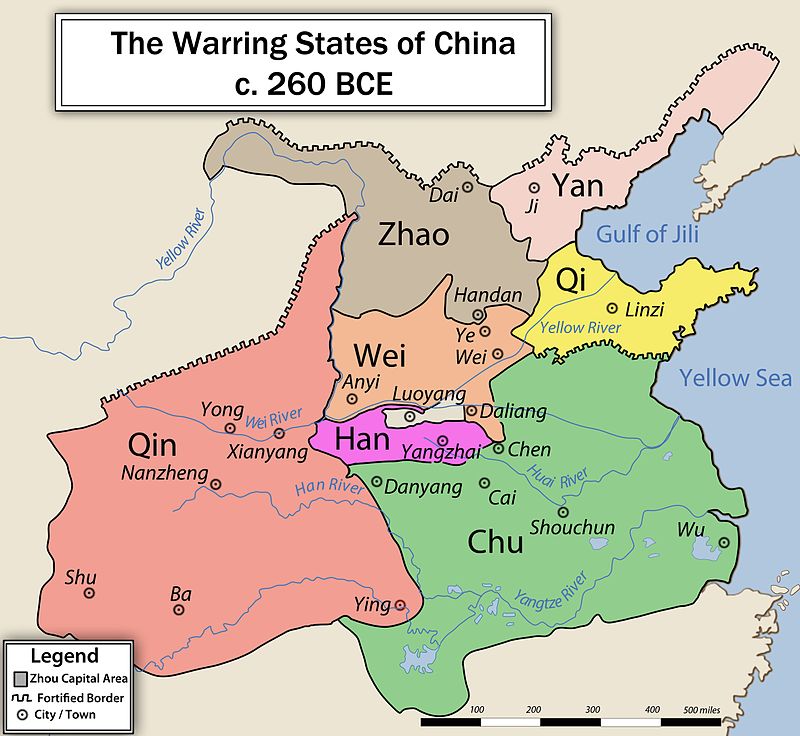

Today it is widely believed that the dragon boat race and the customs of eating zongzi originated from the death of Qu Yuan. Qu Yuan, who supposedly lived from 338 to 278 B.C.E., served as a minister in the southern kingdom of Ch’u, which shared the continent with other two powerful states: the northeastern state of Qi, and the aggressive state of Qin to the northwest.

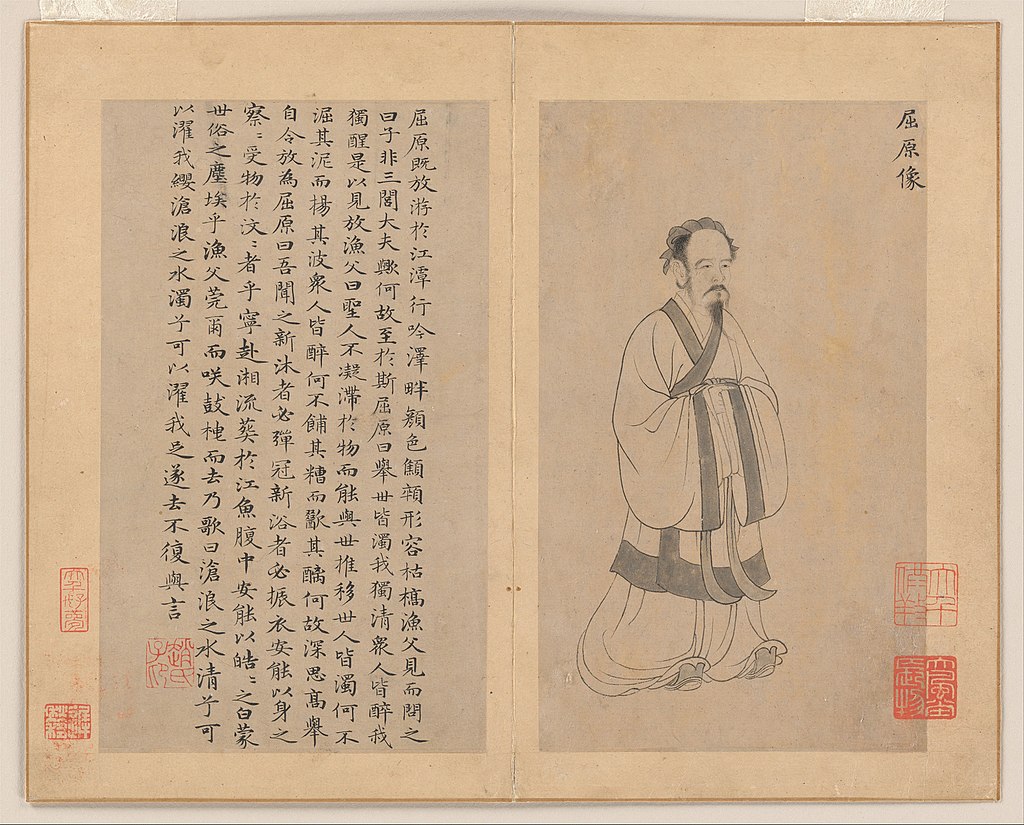

To avoid being devoured by other states and expand the kingdom of Chu, King Huai of Ch’u (329-299B.C.E.) had to find an ally. Qu Yuan suggested the King form an alliance with Qi and together fend off Qin. But the rival faction persuaded the King to work with the militant Qin. As a result, Qu Yuan lost favor with the King and was banished from the court due to rumors spread by the rival faction. In exile, he wrote poetry to emphasize his loyalty to the king and protest his unfair treatment. In 278 B.C.E. when Qu Yuan heard Qin eventually devoured both Qi and Chu, he became completely disillusioned about the fate of Chu. In despair he committed suicide by drowning himself into the Miluo River. Qu Yuan’s dramatic life and tragic death inspired a genre of poetry dedicated to him, called “Chu Ci”. His poem Li sao “On Encountering Sorrow” reputedly written during his exile expresses his resolve to sacrifice his life in the hope of awakening his contemporaries to the truth. Since the Han time, intellectuals and politicians looked at Qu Yuan as a model of loyal statesman who offer advice to his ruler at the risk of losing his career and even life.

Seven hundred years after Qu’s supposed death, Xu Qi xie ji (續齊諧記), a collection of folk legends compiled by Wu Jun (469–520 C.E.), mentions Qu’s association with the Duanwu festival. It says that Qu Yuan died on the Fifth day of the Fifth month and the people of Chu felt sorrowful for his death. Since then, on this day of every year, people put rice into bamboo tubes and threw into water as sacrifices for him. In the eastern Han Dynasty (25-220 C.E.), a personal named O Hui met a ghost who claimed himself to be Qu Yuan. The ghost felt grateful for people’s offerings to him. But the offerings were snatched by a river dragon. To prevent this, he suggested that rice be bundled in chinaberry leaves instead and tied with five-color threads because the dragon was afraid of the two things.

Qu Yuan’s Was Not the Only Tragedy Commemorated on the Duanwu Festival

Zong Lin (502-565 C.E.) in Jing-chu suishiji (荊楚歲時記), a six-century book about festivals and seasonal customs of the Jing-Chu region, pointed out that Qu Yuan was not the only historical figure commemorated on the Duanwu festival,

‘’Cao E Stele’ [曹娥碑] by Handan Chun says: ‘On the fifth day of the fifth month, [Cao E’s father Cao Xu 曹盱] was performing the greeting ritual for [a sacrifice to] Lord Wu [Zixu] 伍子胥. As he moved upsteam against the waves, he was swallowed by the water.’ [Boat racing] is a custom of Eastern Wu also. Zixu is the correct antecedent; it has nothing to do with Qu Ping 屈平(Qu Yuan). Yue Region Biographies [Yuedi zhuan 越地传] says it originated with the King of Yue, Gou Jian 勾践. There is no way to substantiate this.”

Zong Lin enumerates three of the most prominent of drowning victims that were associated with the Dragon Boat festival: Cao E, Cao Xu, and Wu Zixu. He also points out originally dragon boat races were an Eastern Wu (222-280C.E.)custom celebrated on behalf of Wu Zixu(?–484 B.C.E.) and were not related to Qu Yuan.

Like Qu Yuan, Wu Zixu was forced to commit suicide after he gave his ruler Fu Chai, the king of Wu, the unwelcome advice to guard against the deceptions of Goujian, the king of Yue. Historian Sima Qian of the Han dynasty records that Wu requested his eyes be gouged out and hung on the eastern gate so that his eyes could witness the defeat of Wu by Yue. Fu Chai was furious at Wu’s request and ordered to put Wu’s corpse in a leather sack and thrown into the river. After Wu’s death, his kingdom of Wu was seized by Goujian as he predicted. Legend says that the unappeased spirit of Wu Zixu became a powerful water immortal. The local people built temples for the purpose of appeasing his anger and stopping wild waves. By the first century, Wu Zixu became the central of the water-related sacrifices in the lower Yangtze river.

The story of Cao E and her father revealed the transformation of Wu Zixu as a historical figure into a water god. It also showed the association of the Fifth day of the Fifth month with shamanism. Cao E’s father Cao Xu was a musician and shaman. According to folklore, on the fifth day of the fifth month of the year Han-an (143B.C.E.) he was drowned while rowing out towards the oncoming bore to meet the water god Wu Zixu. The filial daughter Cao E searched for her father along the river for days but couldn’t find the body. Cao E gave up and committed suicide by drowning herself in the river. Their bodies appeared together a few days later. Cao E’s act of filial respect drew the attention of the local authorities who erected a gravestone for her.

The above legends shows that worshipping and making sacrifice to water gods predated the death of Qu Yuan. Traditions of making sacrifices to drowning victims or river gods date back to ancient time in China. In his study of Shamanism in ancient China, sinologist Arthur Waley notes the tradition of giving young girls to the god of the Yellow River around 400 B.C.E in Henan, a province in the Yellow River Valley. The purpose of the sacrifice, organized by the shamans who served as intermediaries for gods or spirits, was to please the Yellow River God to prevent floods that might destroy farmland, houses, and human lives.Sociologist Dr. Wolfram Eberhard, who is interested in Chinese folklore, examines the phenomenon of worshipping drowning victims among the tribal peoples in south and east China. In the culture of the Yao people who originated in an area around Hunan and Hubei, river festivals were established to make sacrifices to the drowned women who became benevolent water goddess. They threw into water “fruit wrapped in orchid or other leaves and tied with colored ribbons, as protection against the Chiao dragons.” On the other hand, the culture of the Dai (Thai) people who originated in the province of Yunnan believed the river gods were malicious and had to be appease by sacrifices.

Then when and how did the dragon boat race become part of the fifth day of the fifth month celebration?

Scholarship focusing on the religious origins of the festival argues that dragon boat racing also had its roots in human sacrifices for rain-making rites dating back to the Shang dynasty (c. 1600-1018 B.C.E.). Dr. Eberhard states that the purpose of the boat festival was “to sacrifice humans to the river in order to ensure fertility.” In Chinese mythology, river dragons were thought of as the main deities that took charge of rain, a vital resource for agricultural society. G. Aijmer, a sinologist, argues that the boat festival is related to cultivation of swamp rice in the middle Yangtze valley. In traditional rice cultivation, rice is sown and sprouted in the end of April. Sprouted seedlings are transplanted into water field after 30-40 days. The transplanting of the rice seedlings requires intensive labor and are usually done around the end of May. Aijmer presumes that the boat festival must be performed after the hard work in the rice fields. Therefore, it was a rice planting festival, a festival of prayers for rain and fertility of the young rice plants.

In the fourth to sixth centuries C.E., at least six hundred years after Qu Yuan passed away, old traditions of fertility sacrifice and plague-prevention rites came to be associated with Qu Yuan. The legend of Qu Yuan emphasizes that it was Qu Yuan’s patriotism and loyalty to his king and homeland earned himself the memorialization on the Duanwu festival. However, the aforementioned evidence shows that the locals in the Miluo River where Qu Yuan committed suicide didn’t immediately commemorate his death on the Duanwu festival. As a matter of fact, Qu Yuan’s story was unknown to the general public until ill-fated officials in the Han dynasty tried to restore the spirit of Qu Yuan as a loyal and uncompromising statesman to rescue the declining Han. In the biography of Qu Yuan, Sima Qian, a Chinese historian of the early Han dynasty, identified himself with Qu Yuan after he suffered from expressing dissent and unfair treatment from the ruler.

Today the Duanwu festival is the major summer festival, combining the dual function of commemorating the drowned spirit of Qu Yuan and of ritual prevention of evil influences, diseases, and pestilence brought by the onset of summer heat. The Duanwu festival is not static but ever-changing. It continues to incorporate new rituals and in the forms of folktales.

References:

Alfreda Murck. Poetry and Painting in Song China: The Subtle Art of Dissent. United States: Harvard University Asia Center for the Harvard-Yenching Institute, 2000.

Laurence A. Schneider. A Madman of Chʼu : the Chinese Myth of Loyalty and Dissent. Berkeley: University of California press, 1980.

Stepanchuk, Carol and Wong, Charles. Mooncakes and Hungry Ghosts: Festivals of China. San Francisco : China Books & Periodicals, 1991.

Wolfram Eberhard. The Local Cultures of South and East China. Netherlands: E. J. Brill, 1969.

Wendy Swartz, Robert F. Campany, Yang Lu, and Jessey J.C. Choo. Early Medieval China: A Sourcebook. United States: Columbia University Press, 2014.