The 1918 influenza was the most severe pandemic in recent history. Caused by H1N1 influenza virus, it swept across the world starting in the Spring of 1918 and persisting until early 1920. Although it is known as the “Spanish Flu,” it did not originate in Spain. It is estimated that about 500 million people or one-third of the world’s population became infected with this virus and at least 50 million people died.

Unlike the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID19) that has been much deadlier for the elderly, the 1918 flu affected the 20-40 age group more than any other section of the population. As attempts to make effective vaccines to protect against the 1918 flu infection failed, many Americans who subscribed to the basic beliefs in a scientific approach to health and disease turned to home and folk remedies.

Here are some of the intriguing remedies people used during the 1918 flu pandemic.

Onions Used to Fight the Spanish Flu

In the mid of the fourteen century, the Black Death, an epidemic of bubonic plague, spread to Europe and caused approximately 20 million deaths. Onion was one of the cures people used for the prevention and cure of the plague. Some Europeans chopped up fresh onions and placed them around the house in a belief that the plague was spread through bad smells and onions could purify the air.

In 1665 when England was hit by the Great Plague, London lost approximately a quarter of its population. The plague was caused by rat fleas that carried the Yersinia pestis bacterium, the agent that also caused the Black Death. The Royal College of Physicians in London recommended a mixture made of cooked onions and figs to treat “buboes,” inflamed lymph nodes, on the body of the patients infected with the plague. “‘Take a great onion, hollow it and put into it a fig, rue cut small and a dram of Venice treacle (consisting of vipers, white wine, opium, liquorice, red roses, &c.) close stopt in a wet paper, roasted in the embers.’ This poultice was to be applied to the great tumours which were such a distinctive feature of the plague.”

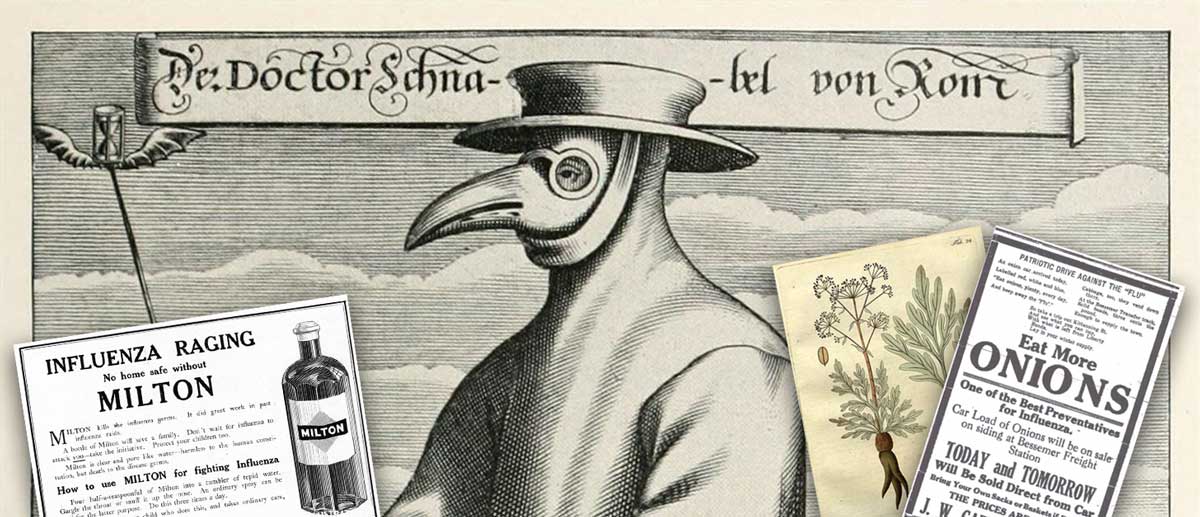

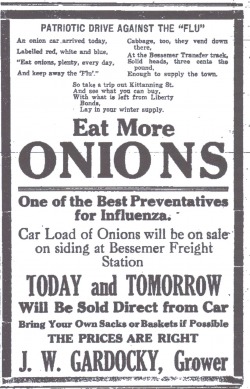

The tradition of using onion for plague prevention probably came to the US with European settlers. In the 1918 pandemic, onions’ healing properties were extolled in newspaper ads and posters. Americans were told that eating more onions was part of a “Patriotic Drive Against the ‘Flu.’ and “One of the Best Preventatives for Influenza.”

In his book on the history of the deadly 1918 flu, Albert Marrin records an anecdote where an Oregon woman “doused her sick four-year-old daughter with onion syrup and buried her from head to toe for three days in freshly cut, eye-watering onions.”

A folklore collection from Adams County Illinois published in 1935 recorded a folk medical remedy probably used in the 1918 plague. The remedy suggests to place onions around the patient’s room so that the virus can “enter” the onions.

The historical view that onions can cure infectious diseases like the flu is overestimated and may not be justified. Today there are still so many people believe in the magic healing properties of onions that the U.S. National Onion Association has to debunk the myth in its Frequently Asked Questions that placing cut raw onions around your house will not prevent diseases.

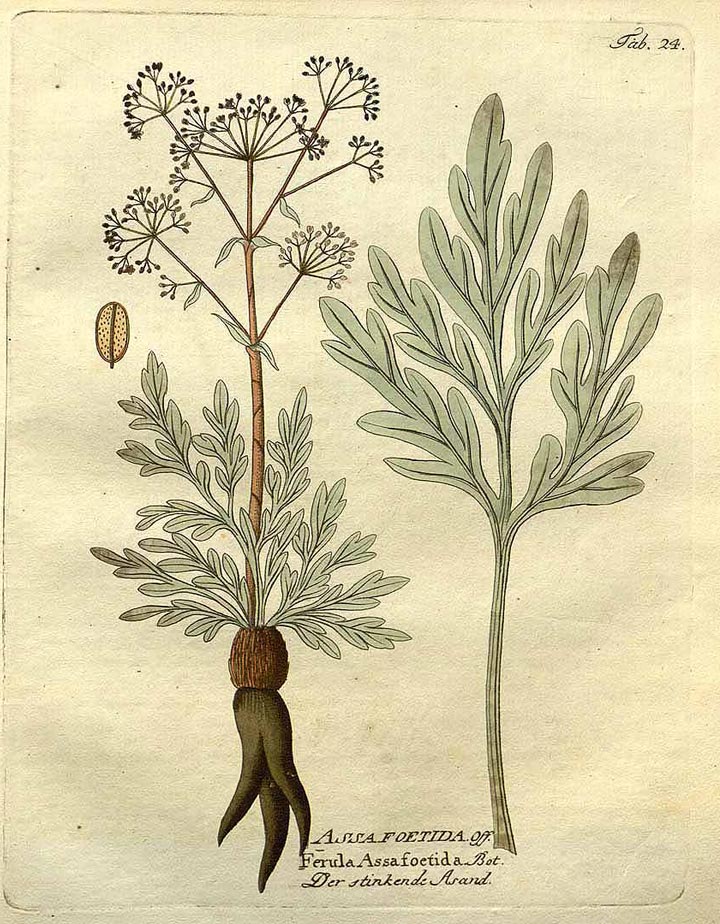

Wearing Smelly Medicine Bags to Ward Off the Spanish Flu

Have you heard of “acifidity bags” before? They are bags filled with healing herbs that usually have a distinct and pungent smell. During the 1918 flu, people who wore them around the neck believed that the bag would protect them from the disease and evil spirits. One of the popular herbs was asafoetid resin derived from the roots of the Ferula asafoetida plant. It has such a fetid smell and a nauseating taste, known as “devil’s dung. In Southwest Alabama, asafoetida was sold out at local drug stores in the fall of 1918. A resident from North Carolina said, “people thought the smell would kill germs. So we all wore a bag of asafetida and smelled like rotten fish.”

Another common substance used in acifidity bags is camphor, a powder from the bark and wood of the camphor tree. Originated from East Asia, it was called “dragon’s brain perfume” by the Chinese because of its pungent and portentous aroma. Camphor was widely used in the preparation of perfumes, fumigants, and medicine in the East before it was introduced to the West probably through trade in Roman times.

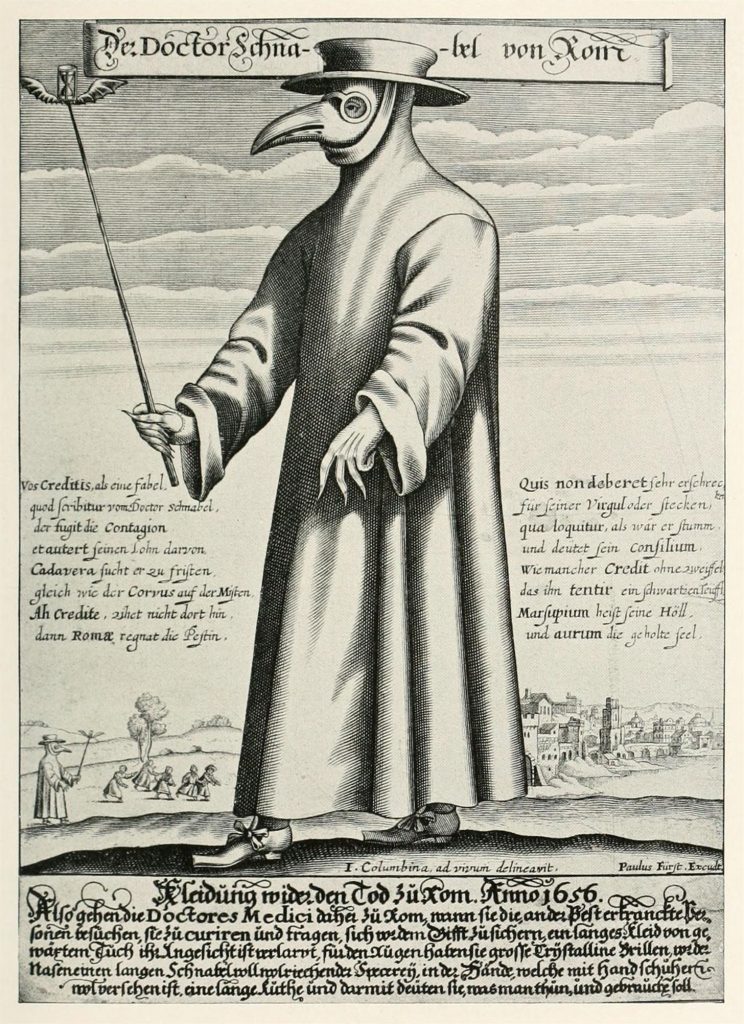

Historical records show that Europeans and Middle Easterners used camphor as a fumigant to ward off the bubonic plague during the black death. Plague doctors believed that the deadly disease was spread by noxious, “evil,” “corrupt” odors. The Medical Faculty of the University of Paris recommended to carry “smelling apples” and “frequently inhale to strengthen the principal organs.” Those “smelling apples” were bags of herb and spice mixture made with black pepper, red and white scandal-wood, roses, as well as camphor. In 1394, residents in the city of Aleppo in Syria tried to protect their homes by burning incense made with “ambergris and camphor, cypress, and sandalwood,” to clean up the “bad air.”

The Plague Doctor Costume, an iconic symbol of the Black Death, had a bird-like beak strapped in front of the doctor’s nose. The beak was packed with powerful aromatics, notably camphor, to counter the “bad air” and protect doctors from being infected. However, there is no evidence that the costume was worn during the fourteenth epidemic. Historians attribute the invention of the costume to a French doctor named Charles de Lorme in 1619. The costume was widely worn by physicians when the plague stroke Europe again in the 17th century.

Wearing a cloth bag filled with camphor was a popular practice during the 1918 pandemic. Photographs from the plague time show children wearing cloth bags around the neck for protection from the dreaded influenza. Shirley Primack Azen, born to a Russian Jewish immigrant family in Canada in 1913, wrote in her auto-biography that her dad made his children wear small bags of camphor around necks to “ward off the Spanish influenza epidemic.” “You must wear the bag of camphor. Do you want to get the flu?”

Drinking Alcohol as a Remedy for the Flu

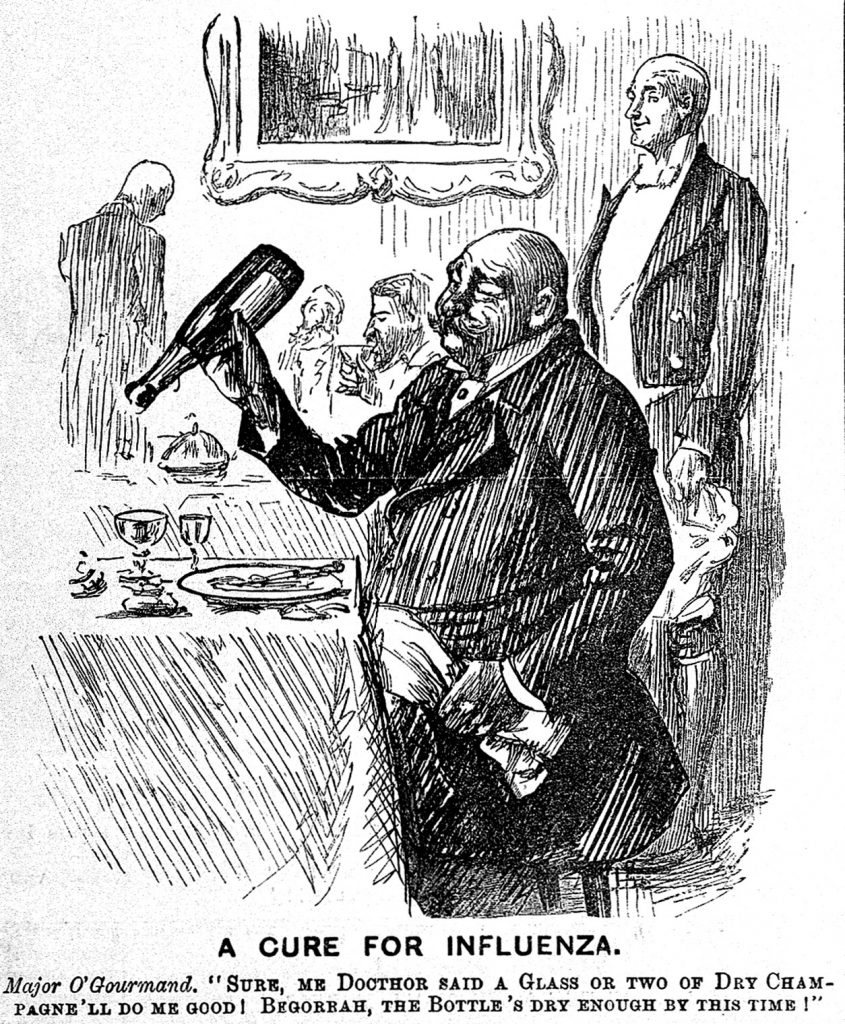

During the 1918 pandemic, doctors were divided about prescribing alcohol as a flu treatment. Without effective medicines and vaccines, some doctors suggested prescribing alcohol to ease patients’ pain and make them more comfortable during the 1918 pandemic.

According to historian Ida Milne, some doctors in Ireland recommended alcohol like brandy or whiskey that were “probably no less worthless than any of the other nostrums, and at least its customers had a merry spin to Paradise.” In retrospect, a French doctor wrote that “…alcohol in all its forms-Todd’s potion, champagne for Europeans, wine for natives—was administered to patients and distributed as a preventative, in the form of rum, to the general public, including Muslims…”

In the U.S., people who believed in the medical values of alcohol resorted to “bottled spirits” during the pandemic. In the April of 1917 when the US entered World War I, wartime rationing on alcohol production and the Temperance Movement made it hard to obtain alcohol. Physicians who advocated alcohol as a “medical stimulant” asked the United States Public Health Service (USPHS) for assistance in obtaining whiskey for medical use. But physicians who disapproved of alcohol for medical purpose supported the closure of saloons during the pandemic.

On October 11, 1918, a public health service physician in Baltimore wrote to Rupert Blue, Surgeon General of the USPHS, asking for a final statement on the use of alcohol as influenza treatment :

“A strong and growing belief exists in the minds of the public in this city and doubtless in other cities as well where Influenza prevails, that alcoholic drinks act a preventative of Influenza. This belief has been strengthened by the attitude of the Health Commissioner of this City, by the non-closure of saloons, giving as a reason that the people should have access thereto in order to obtain whiskey to ward off Influenza. This belief is now so strong among the laity that alcoholic drinks are being purchased and consumed in enormous quantities for the purpose of preventing Influenza. This information has come to my attention from many sources, and the use of whiskey for this purpose is being recommended by a very large number of people, including some physicians.”

PETTIT, DOROTHY ANN, “A CRUEL WIND: AMERICA EXPERIENCES PANDEMIC INFLUENZA, 1918-1920 A SOCIAL HISTORY” (1976). Doctoral Dissertations. 1145.

Commercialized Quack Medicine to Cure All

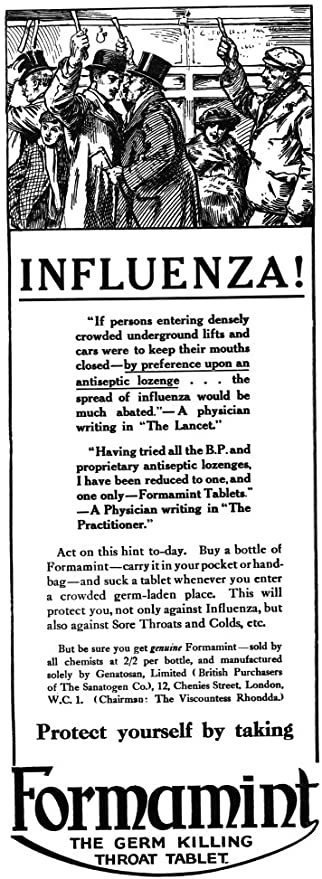

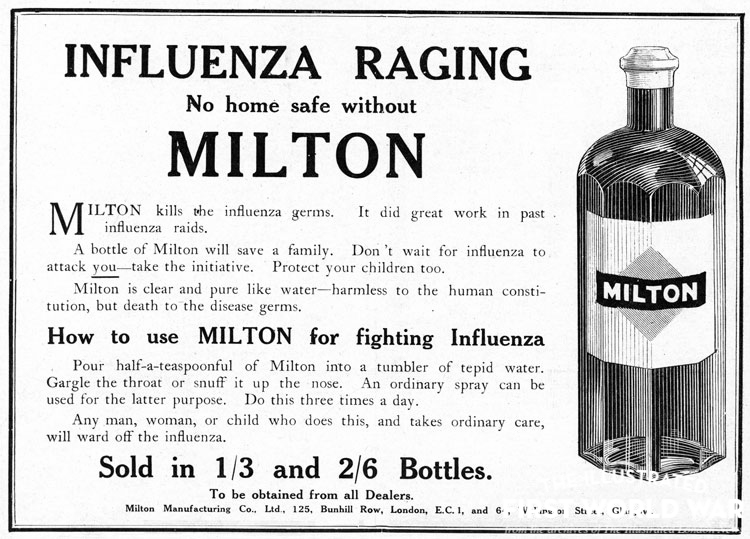

Some private businesses tried to take advantage of the pandemic by promising surprising effect to their desperate customers. Remedies for cold or sore throat were advertised as preventative measures for the flu.

An advert recommended readers to suck a tablet of Wilfing’s Formamint lozenges “whenever you enter a crowded germ-laden place. This will protects you, not only against influenza, but also against Sore Throats and Colds, etc.”

“No home safe without Milton!” proclaimed an advert touting the virtues of Milton sterilizing fluid. It promised that whoever used Milton three times a day to “gargle the throat or snuff it up the nose…will ward off the influenza.”

The Vick Chemical Company in Greensoboro, NC announced in an advert that a high demand wiped out Vick’s VapoRub in a few day. It claimed that VapoRub is effective in treating Spanish influenza. Instructions explained that rub VapoRub on the chest and back of the patient until the skin was red and covered with hot flannel cloths in order to let the body heat “throw off the influenza germs” in the form of vapor. In 2019, Dr. Jay Hoecker debunked the myth about VapoRub in an article published on the website of the Mayo Clinic. He points out that Vick’s VapoRub is not only inefficient in curing nasal congestion but also poisonous.

Familiar food products also suddenly endowed with magic healing powers. Horlick’s Malted Milk was recommended as “THE DIET During and After INFLUENZA.” Broth bouillon companies like OXO and Bovril highlighted the effect of their products on strengthening immune system to fight against the flu.

Religious and Superstitious Cures

Other than relying on professional medical advice or familiar household products, some resorted to religious practice for cure.

In Louisiana the superintendent of a Methodist hospital suggested medical care providers place quilt stuffed with wormwood a aromatic herb and immersed in hot vinegar onto the chest of patients infected with the flu.

In New Orlean, locals sought for voodoo charms to keep the flu away. One voodoo remedy suggested saying a spell three times a day while applying vinegar over the face and palms: “Sour, sour, vinegar–keep the sickness off’n me’.”

The 1918 flu lasted until 1920 after three waves of breakout since the spring of 1918. In 1918, medical scientists were not able to identify the cause of influenza medical science, let alone developing effective vaccines. With no flu vaccines to protect against flu infection, non-medical interventions like social distancing , quarantine, and personal hygiene proved to be effective in slowing the spread of flu, or “flattening the curve.” Comparing how St. Louis treated 1918 flu with Philadelphia shows that social measures were much effective in controlling the pandemic flu when effective vaccines and medicines were not available. St Louis flattened the infection curve by taking a range of measures, such as banning public gathering and closing schools, and controlled the death toll under 700. By contrast, on September 19, 1918, Philadelphia insisted on holding a city-wide Liberty Loan parade when 600 cases were already reported at the Philadelphia navy Yard. By October1, there were 635 new cases and in just four weeks, the city lost over 10,000 lives.

While there are no effective medical treatment and vaccines for COVID-19, I suggest my readers keep social distancing, personal hygiene, and stay healthy at home for the sake of saving life… and take an onion bath for good measure 😉